Ceding Power: Paying the Rest Debt

The final piece in the “Ceding Power” series explores the discourse on rest as a type of reparations. What does it mean to rest and how can the return of energy aid human repair?

The Ostracon: Dispatches from Beyond Contemporary Art’s Center, an arts writing site by Nicole J. Caruth and Paul Schmelzer, looks at figures and ideas outside the mainstream of contemporary art—from public policy, indigenous rights, and folklore to community organizing, historic preservation, environmental science, journalism, and food justice—that may offer insight into new forms of making art that are more responsive, relevant, and connected to the way we live now as individuals and communities. Taking its name from the pottery shards used in ancient Athens when voting to ostracize community members, the site aims to celebrate, instead of push out, voices from art’s periphery.

The final piece in the “Ceding Power” series explores the discourse on rest as a type of reparations. What does it mean to rest and how can the return of energy aid human repair?

“Being Black is exhausting” is a common refrain that doesn’t quite convey what it means to be fatigued on a multigenerational and cellular level. Every day, we as Black folk expend precious energy navigating systemic racism that’s present everywhere all the time. We spend our lives fighting for equal access to healthcare, education, fair compensation, and basic human rights like fresh foods and clean water, all while trying to protect ourselves and our loved ones from being killed for existing. Living in survival mode takes a toll on the body. The spectacle of dead Black bodies on the news and social media takes a toll on the mind. Fake equity initiatives in the workplace take a toll on the spirit.1Mary-Frances Winters, Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and Spirit, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2020.

“When we ask for reparations, it should include everything from economic to energetic repair,” writes the artist Navild Acosta in his 2018 essay, “Cultural Institutions are Colonial Projects, Where’s the Lie.” In this candid critique, Acosta reflects on the experience of being an Afro Latinx, transgender, queer artist navigating predominantly white cultural institutions. His anecdotes are sadly familiar, from expectations of free labor to the extraction of ideas from individuals and communities of color for institutional gain. Acosta articulates a radically different vision for interaction that centers care and repair. “I am imagining a world where marginal people’s rest/sleep/REM cycles are prioritized … Cultural institutions should be instigating better rest/sleep for those who need it most.”

Acosta refers to the racial and ethnic differences in sleep that scientists have just begun to understand. Studies show that Black people have the highest rates of sleeping disorders nationally and generally sleep one hour less than white Americans, Acosta and collaborator Fannie Sosa told a Creative Capital audience. This was the basis of their project Black Power Naps/Siestas Negras, a multi-sensory installation at the Miami Dade College Museum of Art and Design that beckoned visitors to recline on luxurious beds in the gallery to “reclaim laziness and idleness as power.” Black Power Naps explores rest as a type of reparations—the most talked-about non-monetary form of recompense for centuries of racial injustice in America.2According to the Public International Law & Policy Group, “rehabilitation” is a type of reparations that is intended to provide care and services for victims, beyond monetary payments. Rehabilitation can include physical and psychological care, as well as social and legal services, often in a community-focused context. Accessed at: https://syriaaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/PILPG-Reparations-Memo-2013_EN.pdf Across the country, artists, curators, and all sorts of health and wellness practitioners are using cultural spaces, academic institutions, and digital platforms to accelerate what feels like a movement for Black rest aligned with the Movement for Black Lives. But what does rest actually mean in these settings and how can the return of energy aid human repair?

To understand rest in the context of reparations, you first must understand how Black people have been systematically denied the right to respite. (What follows is by no means a comprehensive history.) Chattel slavery forced Black men, women, and children to work 20 hours a day. To maintain control over the Black labor force after the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, Southern states passed a series of laws known as “Black Codes” that led Black men, women, and children to be returned to “slavery-like conditions through forced labor and convict leasing systems that lasted well into the 20th century.” In the state of South Carolina, for example, a Black person who didn’t work on a plantation or as a servant was either taxed for being free or forced into plantation labor for failure to pay that tax. It was a crime to be unemployed or not to toil for the benefit of white men.

Black Codes were repealed in 1866 but subsequent vagrancy laws would make it a crime to be idle “without apparent purpose” or to simply appear suspicious. Modeled after England’s Elizabethan “Poor Laws,” American vagrancy laws have long given police the freedom to deem Black stillness in public space (and sometimes even in private) unlawful. Couple this with anti-Black propaganda, from blackface memorabilia to Hollywood films depicting Black people as lazy stereotypes, and you get a culture that demonizes Black rest. In recent years, this has been hypervisible in mainstream media, from two Black men being arrested for supposedly sitting too long at a Philadelphia Starbucks to a case on the Yale University campus, where a black graduate student found herself answering to police for napping in her dorm’s common space because she didn’t appear to “belong.”

A few months ago, the Oregon-based curator Ashley Stull Meyers and social worker Madeline Harmon launched a community RESTival, a monthlong public program at Reed College in Portland where Meyers and Harmon both work. Open to the public but “birthed for students,” RESTival included lectures, yoga classes, sound baths, and such mostly via Zoom. Mutually energized by the concept of rest reparations, Meyers and Harmon began dreaming of ways to facilitate “community and joy and wellness” for students representing marginalized identities on the campus.

“We were thinking about this tiresome moment that as Black and Brown folks we’ve always been in but especially the past four years as a Black or Brown person engaged in diversity, equity, and inclusion work, activism, and education,” Meyers said. “It just doesn’t seem there’s respite to be found anywhere. It’s this awkward negotiation of there being so much work to do but also understanding that we’re not going to survive this moment if we don’t also take little moments to care for ourselves in real, logistical ways.”

As Meyers told me about “diverting institutional resources” to make this happen, I thought about the extra labor Black women so often do to support the health and wholeness of other people of color. What if the system was set up so that we didn’t have to be double agents in institutions, genuflecting to white comfort so we can serve people who like us? What if we didn’t have to do twice the labor to express care for the people we care about? The health coach in me couldn’t resist asking Meyers about her personal relationship to rest. “It’s tough,” she replied with some heaviness in her voice. “The art world and culture work of all kinds is always moving, and it’s hard to take a minute to take a step back from it.”

RESTival shifts the paradigm of typical arts wellness programming from the instagrammable performance of care to somatic healing practices for the inner repair of human beings. Sadly, this way of thinking is radical in our cultural institutions. I queried further, how else might rest reparations look? What other models might we reimagine? Meyers mentioned artist residencies for their ability to provide time and space to think without the expectation of artists producing a tangible object. “Outside of an art world context, that’s what rest as reparations looks like to me,” she says. “Space to think—we need more of this.”

What’s more important than a specific structure as a reparations framework are the attitudes and behaviors that guide what happens in the structure. “There’s been unconscious expectation that Black folks are going to be cultural contributors even in moments where we’re not meaning to be,” says Meyers. “Even when we’re talking about Black kids on TikTok who don’t necessarily conceptualize what they’re doing as culture work. For me, rest as reparations looks like the right to some sort of opacity when we want it.”

RESTival was inspired by Tricia Hersey, a multidisciplinary artist with a master’s degree in divinity and founder of The Nap Ministry, an organization that creates collective rest experiences to explore the liberating power of naps. Hersey is an undeniable influencer of millenial self-care, rallying her Instagram troops to reject the false urgencies of white supremacist culture by slowing down and opting out. What began as a performance art project Hersey now describes it as a “spiritual and political movement.” Hersey’s definition of rest encompasses anti-capitalism, daydreaming, storytelling, afrofuturism, somatics, community care, womanism, sleep science, and reparations theory. “Resting is simply a connection between our mind and bodies,” she explained to a Zoom audience at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia). “It’s a slowing down. It’s a reimagining. It’s reclaiming our time as our own. It’s slow living. It’s daydreaming. It’s drinking our tea a little bit slower in the morning before we start the grind race. It’s making space for others to rest.”

But how is taking time for yourself an act of reparations? Hersey suggests that by taking the time to rest that was denied our enslaved ancestors we can begin to slow the capitalist systems that do us physical, mental, and spiritual harm. There is a rest debt to be paid and we can claim what is owed through napping.

“Everything in this culture is for us to go, go, go,” said Hersey. “From the plantations back in the South when slavery was invented, and when capitalism was invented in those fields, that energy is still [here] now. That automated way of looking at a body as a machine, that way of looking at property and profit over people, all of these things are deeply entrenched in our society.” Hersey has made clear that her message is for everyone, regardless of race, because the belief that exhaustion is normal and necessary for productivity is a lie of capitalism that we’ve all been conditioned to believe.

Rest, as Hersey beautifully describes it, is a lifelong “meticulous love practice” of healing and decolonizing our bodies and minds from centuries of violence. Black people aren’t the only ones who have ancestral healing to do. On an episode of the Irresistible podcast, Hersey conjured the image of a lynching to make a point I’ve heard repeatedly this past year: What kind of trauma makes a man so spiritually bankrupt that he takes his children to celebrate the lynching of another human being? That poverty of spirit lives in white bodies today because all of our bodies carry, as Resmaa Menakem writes in My Grandmother’s Hands: “The unhealed dissonance and trauma of our ancestors.” The process of reparations, then, is entangled in the spiritual repair of white Americans who must do the work to understand how white supremacy harms them, too.

The Black Power Naps theory of rest reparations emphasizes making space for quality sleep.” Which begs the question: what exactly is keeping us up at night? Studies on ambulatory blood pressure offer a clue. As Dr. David R. Williams, a leading scholar on health inequalities and professor at Harvard’s TH Chan School of Public Health explains, these studies show no differences between young, healthy African Americans and whites during the day. However, researchers found that African Americans maintained a higher level of blood pressure at night, even during sleep. In reviewing this data, Dr. Williams asks, “Could this reflect the possibility that the threats in our environment, potential threats of violence, potential threats of discrimination, is so high that it’s almost as if African Americans need to sleep with one eye open?” The case of Breonna Taylor has confirmed this much: not even in sleep are we safe.

At this point in my writing on reparations, I know that some white arts workers want easy answers to soothe their discomfort and avoid the inner work that equity asks of them. (I’ve read enough emails confirming as much.) In the absence of care and criticality, I can imagine institutions responding to this call for rest by organizing programs to advance a theater of equity that ends up reinforcing stereotypes. Yet I struggle to understand how those who hold power can give rest responsibly. What could rest reparations look like as concrete institutional action? Acosta and Sosa suggest that it’s less about doing than unlearning: “To center the sleep of Black folk, you must not economize, commodify, or extort it.” Since the Middle Passage, white people have had “unfettered access” to the Black body. Black folks can’t rest until that unconscious mindset changes, which feels a long way off.

Black people are often expected to be the voice of diversity in predominantly white cultural institutions, to do the labor of educating white people about racism, no matter the mental and emotional drain, while meeting our everyday job expectations. We’re given the same (and sometimes more) responsibilities as our white counterparts but with less pay or compassion for what it takes to get the work done. Anecdotally, a colleague recently shared with me that a white curator sitting at his desk and behind on deadlines is perceived as doing the “thinking work” his job requires, whereas she, a Black curator, is perceived as sitting idly and expected to pick up his slack. The “Black Codes” of the nonprofit workplace, a set of unofficial rules for Black people, show up in all kinds of ways. In my own experience, after a series of racist incidents at a previous job, the executive director instructed me to “smile or things wouldn’t be good for me”—to mask my emotional fatigue and tap dance to prevent punishment. It’s not being Black that’s exhausting; it’s the systemic racism, social stigmatism, discrimination, and indifference that plays out even in so-called progressive art spaces and institutions.

Frontlines of All Kind, a documentary film about the Black Power Naps opera, premieres tomorrow, March 3, 2021 at 1pm EST, as part of the Ford Foundation exhibition, Indisposable: Structures of Support After the Americans with Disabilities Act. The film will be followed by a moderated conversation and soundscape meditation with the artists.

What’s the difference between a donation and reparations? In this second piece on reparations in the arts, Brandi and Carlton Turner, co-founders of the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production, share their perspectives on charitable gifts and possibilities for change in arts philanthropy.

Just a few months ago, the news cycle was filled with stories about Silicon Valley companies pledging five- or six-figure donations to support the movement for Black lives. It’s rare to see an artist come close to matching anything that tech companies can give at a moment’s notice, but the musician Jeff Tweedy announced that he would commit five percent of his writer royalties to racial justice organizations in perpetuity. The Wilco frontman, who’s worth an estimated $9 million, encouraged other white musicians to do the same because, as he suggested in a written statement, the music industry continually profits from the appropriation and theft of Black creativity and culture. “The wealth that rightfully belonged to Black artists was stolen outright and to this day continues to grow outside their communities,” he wrote. “No one artist could come close to paying the debt we owe to the Black originators of our modern music and their children and grandchildren.”

I’d never heard of Wilco or Tweedy until his statement began circulating online, so I’m literally not a fan. What got my attention was his simultaneous call for industry-wide reparations—and that multiple white colleagues of mine understood Tweedy’s pledge to be reparations itself. This prompted a question that I’ve been posing in interviews: What’s the difference between a donation and reparations? Is there a specific dollar amount or giving strategy that makes the leap from tax-deductible gift to reparative justice?

Few people have a clear answer, except Brandi and Carlton Turner, the husband and wife co-founders of Sipp Culture, known formally as the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production. “You think about breakfast. You have eggs and some bacon and some toast. The chicken made a donation, the pig made a commitment,” Carlton said with a chuckle, repeating the words of a former coworker. “There’s a sacrifice that has to happen that is related to reparations whereas a donation [implies that] ‘I can keep giving this donation because I’m not really hurting from it.’ A donation doesn’t change the power dynamics. It doesn’t equalize power. It just quells disruption is what donations do. What reparations does is it actually alters power.”

Established in 2017, Sipp Culture is an enterprising model of what we might call creative placekeeping in Utica, Mississippi. Their work spans three spaces all within walking distance to each other, including a 1920s-era house for an artist residency program, 17 acres of land for a demonstration garden and outdoor amphitheater, and a cultural center on Main Street that serves as a community hub. But listen to the Turners tell it and Sipp Culture is far more than a cluster of programmable spaces. It’s the coming together of Carlton’s lineage, which goes back eight generations in Utica to a plantation and the enslaved Africans who worked that land; his background as a performing artist and cultural leader (he was previously the executive director at Alternate Roots); and the manifestation of he and Brandi’s vision to share the stories of this place they call home.

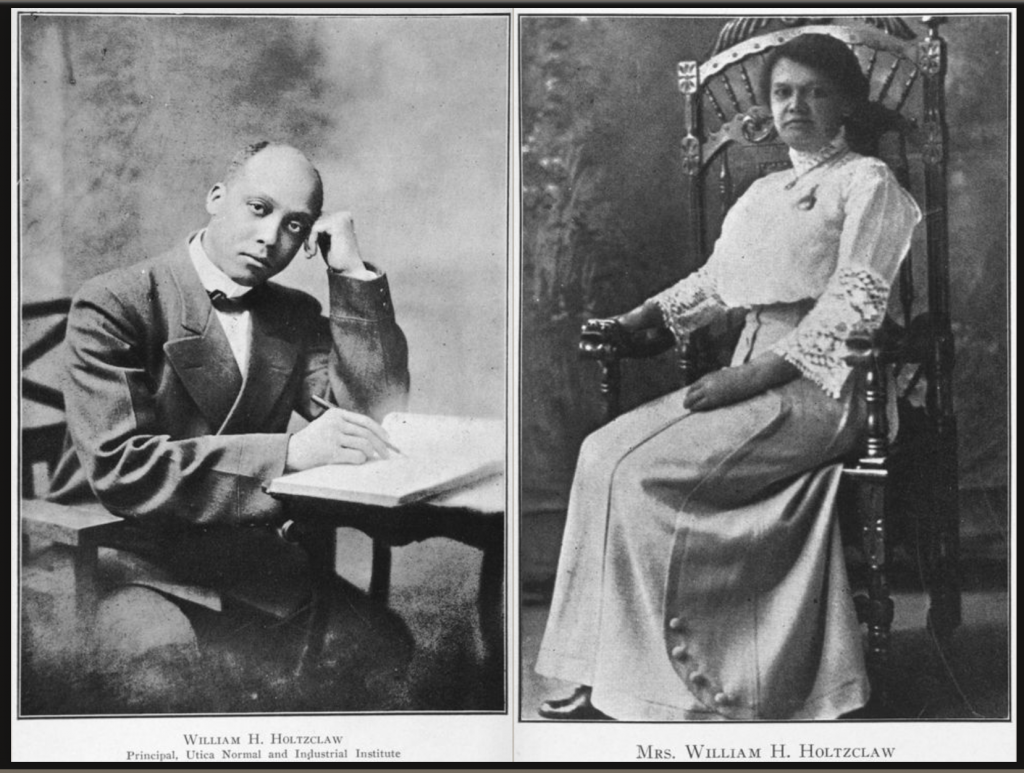

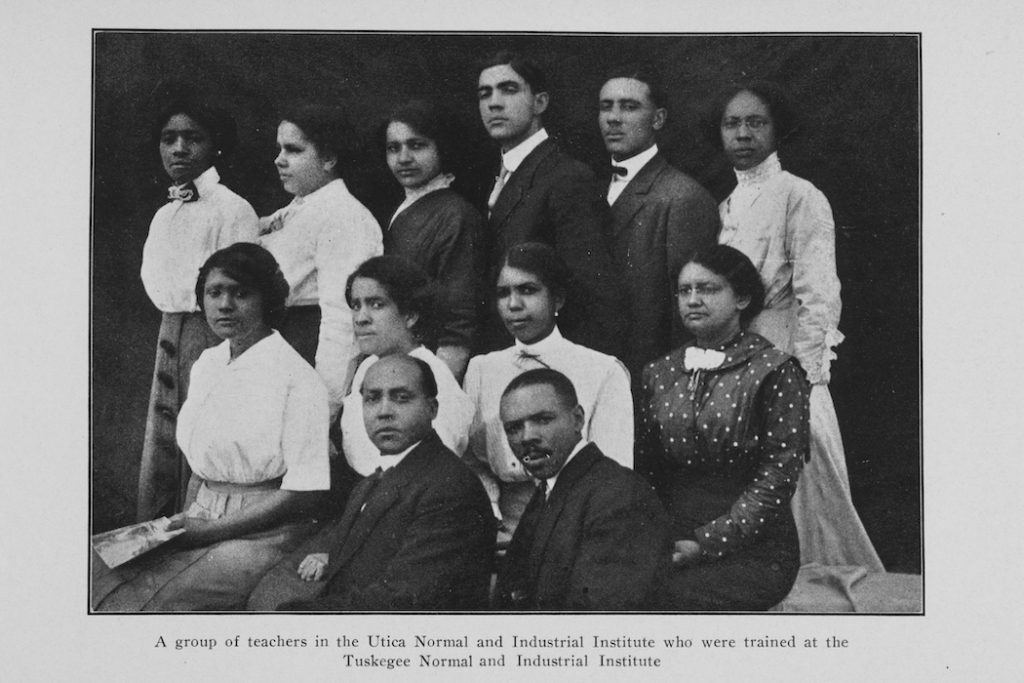

Once a hub for cotton production and export, “Utica [Mississippi] was created by white people coming down from Utica, New York, and developing a kind of settler space here,” Carlton explained. “The Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Natchez people were in this area.” Sitting next to Brandi at the Sipp Culture site, he told me how, in the early 1900s, a man named William Holtzclaw, a student of Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, established the Utica Normal and Industrial Institute.1See more images of the Utica Normal and Industrial Institute in the New York Public Library Digital Collections. The school eventually became Utica College, the first and only historically black junior college in Mississippi, and also housed a high school. “They created this infrastructure to support the post-reconstruction era, to support the education of Black people, turning them into educators, business people, administrators, and agriculturalists,” he said. “You have probably three generations of people that came to that Institute and became the Black leadership in and around central Mississippi.”

In recent years, Utica has witnessed the closure of its grocery store and high school, creating deep cavities in the public infrastructure that are increasingly common in Black rural and urban areas alike. Brandi said, “When we started thinking about our work here, it was about creating a space in our community that served our community.” Sipp Culture operates at an intergenerational crossroad, looking forward to the future of Utica for its young people while looking back at the historical events that can still be felt today. For instance, the white terror that precipitated the Great Migration and affected the ability of Black families to pass land to their family members. “When you think about reparations,” Carlton added, “our work is about repairing some of that generational damage, and connecting people back to a legacy and history of agriculture, of growing and producing, but not producing for someone else, producing for the community and for collective liberation practices.” The Turners also see their relationship to reparations as “repairing ideas” about the boundaries of art and culture by honoring practices typically excluded from the narrow definitions of what art is.

Sipp Culture is one of several organizations involved with Reparations Summer, a campaign of the National Black Food and Justice Alliance (NBFJA). Reparations Summer promotes a “new Juneteenth tradition” of annually organizing and redirecting resources back to Black land stewards. The website states: “We demand that white people and folks with access to the accumulated and hoarded resources move money and land out of the extractive economy now so that we can plant it as seeds to grow the Reparations strategies we need to become truly whole.” Bearing images of Black farmers alongside unapologetic statements about what is owed, the Reparations Summer website is visually appealing but feels untended and untethered from the action. The campaign came to life for me after hearing directly from the Turners, who revealed multiple connections between the organizing efforts of NBJFA and the systems that fund the arts.

When I asked the Turners where reparations might begin in the arts and culture sector, Carlton gave a compelling response:

I think so much of art and culture relies on heavy investment from philanthropy and that’s a troubled relationship because most of the surplus resources that are stored in the form of endowments, and the way that philanthropy is structured, so much of that money came on the backs of enslaved people . . . These foundations were created as tax shelters and allow these wealthy institutions and trustees to still determine where those dollars go. Otherwise, those dollars would be in the public coffer and would be distributed as democracy dictates, whatever that means . . . But that’s not the case. Foundations are structured to live in perpetuity. That’s literally written into most foundation charters. So, I think reparations, for me, looks like challenging ideas about these dollars being held in perpetuity and thinking about how these philanthropies can begin to spend down and into non-existence.

This almost made sense to me. As someone who’s worked almost exclusively on the public programming side of the visual arts, having little contact with funders, my knowledge of how philanthropy actually works is minimal. So, to better understand it, I did what most learners do these days: I turned to YouTube.

Last month, Vu Lee of Nonprofit AF moderated a virtual panel discussion called “What’s Broken in the Foundation and Donor Landscape?,” an eye-opening dialogue on how foundations hold wealth and power in society. Speaking to an audience of 1,300 live viewers, Chuck Collins of the Institute for Policy Studies said, “The purpose of this conversation is to open up this invisible, mostly secret world of how high finance works.” The panelists, including Edgar Villanueva, author of Decolonizing Wealth, and Andrea Caupain, CEO of Byrd Barr Place, explained that private foundations must give out a minimum five percent of their endowment annually. “It is intended to be the floor and that has become the ceiling for most foundations,” said Villanueva. He then echoed what Carlton had begun to illuminate: “Despite our role in helping to create this bounty of wealth in this country, off the backs of our ancestors, and the current day expectations of lower-wage workers [who are] mostly people of color, we as people of color are not benefiting from our fair share of philanthropic investment.” Of the five percent minimum that Villanueva mentioned, a meager 8–8.5 percent go to communities of color, even as racial inequities in healthcare, education, and housing widen and nonprofits work to fill these gaps.2Watch the second part of this conversation on philanthropic reform, “Fixing Philanthropy for Communities,” which addresses potential solutions.

Hearing this dialogue left me with the same question for arts philanthropy that I have for the arts at large: What models get beyond all the buzzy verbiage about diversity, equity, access, and inclusion to actual transformation? Or even reparations? In speaking with DeeArah Wright for my last Ostracon piece, she held up the Leeway Foundation in Philadelphia, which gives grants to individual women, trans, and gender nonconforming artists, as one model to which others might aspire. Denise Brown has been Leeway’s executive director since 2006, following a strategic shift that moved this small family foundation from a predominantly white staff to majority people of color on the staff and board of directors. Leeway Foundation worked with community advisors, which included artists, to design a new application that focused on formative personal, political, and artistic experiences as opposed to your typical signifiers of value like CVs.

In Brown’s mind, the Jeff Tweedy example speaks to the problematic relationship that the Turners alluded to: The power to determine how much money will be given and who it goes to remains with the white man who holds the wealth. “What turns it into reparations is how much agency and autonomy those people have who are supposed to benefit from his decision to give resources,” said Brown. “What is their role in defining what that looks like? That is when it starts to veer more towards reparations. Until then, it’s just a charitable impulse.”

Brandi Turner suggested to me that reparations must involve systemic change that “serves us as a whole, as humans.” However, arts funders have a tendency to shift their priorities to support trends—arts engagement in low-income neighborhoods, DEAI training in museums, or COVID relief for artists, for example. I’m not suggesting that support is not needed in these areas but there’s little indication that these philanthropic dollars dismantle systems that uphold injustice, or alter power structures, or close the racial wealth gap, or mend the decades of underfunding, disinvestment, and destruction in Black communities. A donation is, to paraphrase one of my students, akin to using a tourniquet instead of repairing the actual wound. “Most of these large philanthropies are not progressive enough to see how they could help to foster and sustain the type of change that’s needed in order to have a different type of world,” Carlton told me, “Even though a lot of them have the equity and diversity language, that only goes so far.”

Reparations for Black Americans can take many forms. What might this look like in the arts? This post kicks off a conversation series with artists and culture-makers about the possibilities for distributive justice in the arts to repair the historical and ongoing damage of anti-Blackness.

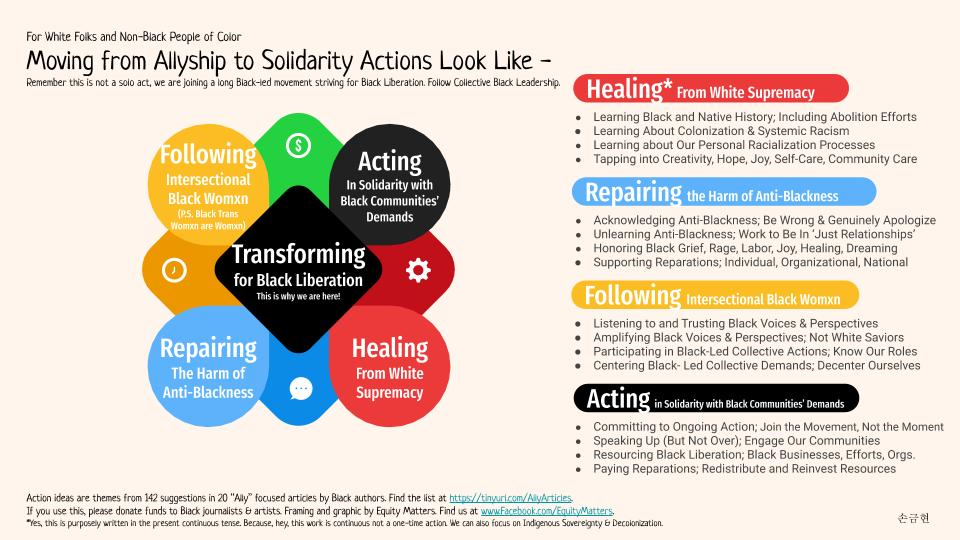

In the weeks following George Floyd’s murder, white-led institutions and companies of all sizes published Black Lives Matter statements, declaring solidarity with their Black staff and constituents and committing to anti-racism. Now that the period of platitudes has subsided, I wonder which arts institutions are engaged in the daily and deeply uncomfortable work of undoing racism? Who in our arts communities is performing allyship and who’s actually relinquishing power to advance Black liberation?

In the arts, we’re awfully good at intellectualizing injustice, studying and theorizing how we got somewhere as a society while failing to recognize how our own institutions perpetuate and benefit from brutality against our fellow human beings. Our arts leaders are swift to write empty inclusion statements, organize panel discussions on social justice, and publish white papers on diversity and equity strategies that took years to develop. But they are slow to take action, with boards and bureaucracies serving as excuses or real obstacles to structural change. And why should we expect more when so many cultural institutions and the people who fund them built their fortunes on the backs of enslaved peoples, by pillaging not only their artifacts and ideas but by stealing their land and lives? Maybe this is why the discourse on reparations for Black Americans sits on the periphery of the arts feeling as taboo as P-Valley is to Hollywood, as sidelined yet as present as Colin Kaepernick.

Repair from the harm of anti-Blackness requires action, not a social media statement about how you intend to behave or what you want the public to believe but actual sacrifice. As Leah Penniman, co-founder of Soul Fire Farm, explained in our interview earlier this year:

“There’s a misconception that the main issue with racism has to do with how individuals treat each other. In other words, ‘be nicer’ when, actually, the main issue with racism is institutional or structural. We can’t solve racism by teaching tolerance or helping people be nice. We solve racism by giving over the lands, the money, the positions of influence in organizations and government and then we share those fairly in society. It’s not about intention; it’s actually about the outcome. We’ll have racism until all metrics of the distribution of power and resources don’t have racial differentials.”

Soul Fire Farm operates with a reparations framework, which means the farm not only acknowledges “that labor was taken, that land was taken, that resources continue to be taken,” says Penniman, they teach folks “to give them back without the associated social capital or ally bash. Just give them back because it’s the right thing to do.” Penniman has seen this emphasis on action in their Uprooting Racism workshops lead to “some pretty profound change,” from “small acts, like well-resourced organizations dedicating twenty percent of their grant writer’s time to writing grants for frontline Black and Indigenous-led organizations that need that support without fanfare, up to giving away ten acres of land.”

This got me thinking: What forms might reparations for Black Americans take in the arts? What’s our twenty-first century version of 40 acres and a mule? How might reparations in our sector support the larger-scale systemic change needed in, say, housing, healthcare, and education? How are artists and culture-makers envisioning reparations in their creative corners of society, from farms and restaurants to museums, performance spaces, and publishing houses? And what platforms are being used to advance these visions? In this conversation series, I attempt to get answers to these questions.

In February 2017, the New York performance venue JACK launched Reparations365, a series of performances, workshops, and conversations about distributive justice for Black Americans. The timing of the series was accidentally perfect: Trump had recently been sworn into office, and Congress had just introduced the H.R.40 bill to:

Address the fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery in the United States and the 13 American colonies between 1619 and 1865 and to establish a commission to study and consider a national apology and proposal for reparations for the institution of slavery, its subsequent de jure and de facto racial and economic discrimination against African-Americans, and the impact of these forces on living African-Americans, to make recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies, and for other purposes.

Really, what better time to start a community forum on reparations, “the single most divisive idea in American politics,” than after the election of the most divisive president some have seen in their lifetime? As JACK put in its website, “In the aftermath of the [Trump] campaign, the idea of reparations feels both absolutely improbable and absolutely necessary.”

Reparations365 started with JACK co-founder and co-director Alec Duffy, a cis white man, who brought the idea to his co-director at the time, DeeArah Wright, a cis Black woman who now sits on JACK’s board. Duffy was inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates’s article, “The Case for Reparations.” I got the sense that Wright was on the fence about the topic at first. “My work and activism in arts and education is more powered by a sense of self-determination, not consistently looking to this idea of reparations,” she told me via Zoom. “I’m definitely for reparations but I was interested in shaping something that felt like a non-prescriptive way of thinking about it. How could we facilitate this conversation in a creative way, incorporating the arts in thinking about what it means to repair? We thought a lot about how artists are always deconstructing something and creatively putting it back together in ways that make sense for our community; really thinking about what we have and then using that to assess what do we really need and what do we truly want?” So far, JACK has hosted more than 40 conversations on reparations, and Wright has moderated all but one. Participants have ranged in age, from 17 to 70ish, and racial and ethnic backgrounds, though most participants have been Black.

People hold such strong opinions about reparations that discussions on the topic tend to get contentious, even in my own family. What was it like to moderate an interracial, intergenerational dialogue on reparations with strangers who haven’t been indoctrinated into the politically correct conventions of arts dialogue? “There were plenty of uncomfortable and a few volatile moments,” Wright recalls. One disharmony stood out to her: Participants often had difficulty “finding the balance between actively listening and being triggered when people talked about how systematic oppression and racism have impacted their lives.” This meant “being able to sit with some really uncomfortable truths.” Other tensions arose around logical but complicated questions: Who is responsible and accountable for reparations? Who should be trusted in the work? Whose job it is to do the heavy lifting, Black or non-Black people? From Duffy’s perspective, “there’s a lot of mistrust in white people doing that work for Black people,” he said. “How are we ensuring that it’s not just white people trying to solve problems again? We’re always wanting to have the solution and that has often turned out very poorly.”

Located in a former garage space in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill neighborhood, JACK was co-founded in 2012 by Duffy and several of his colleagues. They wanted to create a theater that, as he said, “reflected the diversity of New York City and felt like it could be a home to our neighbors.” Duffy and his wife used their savings of $75,000 to start the space, and “the money ran out after about five months.” By that time, they were making just enough from ticket sales and rentals to keep JACK going, though never sure if they’d make the next month’s rent. “All sorts of people started coming into our orbit that wanted to program dance and have their own music concerts,” said Duffy. So, JACK quickly evolved into a multidisciplinary performance venue.

The murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner two years later marked another turning point at JACK. “There were protests coursing through New York City and I was asking myself how JACK could provide support to this movement for racial justice at this particular moment.” Duffy’s response was “Ferguson Forward,” six months of programming on racial justice that incorporated benefit parties for local activists. The public response to the series helped Duffy realize that “JACK was not just a space for performance, but a space for activating our community around critical issues of the day.” Motivated to dig deeper into racial justice, Duffy knew, as he told me, “it was pretty problematic for a white male to be leading the visioning around that.” So, instead of using a grant he’d received to hire JACK’s first development director, Duffy hired Wright, an artist and organizer he’d gotten to know in the neighborhood.

“How do we make our organization reflect the values that we’re talking about in the reparations series?,” Duffy said. “By sharing and being in solidarity with people of color and making sure that the leadership of JACK is not just white-led. That influences everything I’m doing on a daily basis in terms of our work with programming, fundraising, partnerships, building relationships in the neighborhood, thinking about what conversations we want to frame at JACK, and how we want to have an impact on our community.”

Anyone can make a declaration of solidarity on behalf of their institution, but our true values show up in how we treat people and in the choices we make outside of work. When I asked Duffy how Reparations365 has impacted his daily actions, he stumbled a bit, saying, “I don’t have an individual reparations practice yet. I haven’t yet been bold or brave enough to go there.” He began reflecting on JACK’s forum on the intersectionality of reparations and parenting: “It ended up being about how white parents can make sure they’re not contributing to racial injustice in the way they raise their children . . . As a newish parent myself, with toddlers, that’s very much influenced what I know will be our next 10 to 15 years of decision making. Now, is that reparations? I’m not sure.” I’d argue that it’s not, but it’s lovely nonetheless to think of child-rearing as a series of actions driven by desire to repair the harm of anti-Blackness, not the so-called progressive teachings of tolerance. The true test of Duffy’s commitment will be the consistency of his actions as his family needs change over time.

Wright and Duffy have different visions for reparations in the arts, but they align around the idea that there has to be organizational restructuring to even start a larger conversation on reallocation. Wright (who is now director of Education at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum) says, “There are so many ways that reparations could look on a personal or organizational level,” yet she offers this recommendation inspired by Reparations365:

“White-led and founded arts organizations can make ongoing and active commitments to unpack their organizational history, publicly acknowledge how they have benefited from oppressive systems and white privilege, and make a related public pledge to reparations. Active reparations within the organization could include offering Black team members reparative offerings to support their work-life flow, like additional paid personal days and a chosen, flexible work schedule. Arts organizations could also ensure that Black and Indigenous folks are in empowered positions on the board and leadership team, even if this means white team members must step away.

All folks who want to be an active part of reparations in the arts could complete an ongoing combination of anti-racist training, accountability practice, and direct action, such as committing to paying down or paying off a Black artist’s student debt; offering no-cost services to Black artists; or, transferring ownership of land and spaces to Black and Indigenous artists and organizations.”

Wright seems optimistic about reparations but, true to her spirit of self-determination, she’s looking ahead to the homestead cooperative—“an ecosystem of land co-stewarded by Black and Indigenous members who thrive and create home together”—that she and her husband are launching in upstate New York.

Meanwhile, Duffy is focused on the nonprofit racial leadership gap. “We’re thinking a lot in arts orgs right now about succession planning for leaders because there are a lot of white-led arts organizations and so what does it look like in the context of this current movement?” Duffy is one of 40 New York–based arts leaders that participated in an Undoing Racism workshop led by The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond a few years ago. This cohort, which is racially mixed but mostly white, began meeting regularly when the recent wave of Black Lives Matter protests began.

“There’s talk about transferring power, shifting power, and shifting relationships. It’s never been talked about necessarily as reparations but more like, ‘This is the healthy way for our organizations to develop,’ that we need more voices of color in our highest leadership positions.” But Duffy finds that some of his peers don’t see racial inequity (let alone reparations) as their problem to solve. And let’s be honest, even the most well-intentioned folks can be in succession planning mode for years with zero sense of urgency to move on.

Whether Black arts leaders will want positions that white leaders now hold raises a host of other questions. Does the salary match or exceed what white workers are being offered? (Efforts to reduce the racial wealth gap through salaries could be a form of reparations.) Where is the job located, and are the residents hostile toward Black bodies? Will new Black leadership be embraced or embattled by the staff and board? What’s the financial health of the organization that’s being handed to the successor? Would it be better to build a new organization with equity at its core or try to turn someone else’s ship by doing the exhausting work of changing hearts and minds? “I guess another tension is that some Black arts organizations that I’ve been in contact with are like, ‘We don’t want to sit at your table,’” said Duffy. “‘We created our own table.’”

Ceding power to Black leaders isn’t reparations. However, it is part of a reparations process in a sector that’s controlled by white wealth and largely caters to its wants and whims. This is not to say Black leadership can’t reinforce the values of whiteness but we at least need more opportunities to lead. If we can’t get a seat at the table and the power to make decisions, how are we going to create the conditions in the arts for reparations to occur?

Leah Penniman, the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm and author of Farming While Black, talks about healing from generations of land-based trauma and creating a more just food system.

Years ago, when I just began to learn about food justice, I volunteered to help out at a youth-run farm in Brooklyn that had been devastated by a storm. As a thank you to the volunteers, we received a free workshop on garlic at the end of the day. I don’t remember one iota about planting or harvesting garlic, but I’ve never forgotten how the workshop leader, a young white woman, responded when someone asked why the predominantly Black youth who worked there lacked access to healthy foods. “Nothing in the food system happens by accident,” she replied. In other words, unequal access is by design.

Our food system is inseparable from the larger social, economic, and political institutions that place power in the hands of a privileged few while others go without.1Eric Holt-Giménez and Breeze Harper, “Dismantling Racism in the Food System,” Institute for Food and Development Policy/Food First/Food First Books, Number 1, Winter-Spring 2016. https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/DR1Final.pdf Leah Penniman, the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm, calls this “food apartheid—a human-created system of segregations, which relegates some people to food opulence and other people to food scarcity.”2Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez, “How Do We End ‘Food Apartheid’ in America? With Farms Like This One,” AlterNet, June 12, 2017, https://www.alternet.org/food/how-do-we-end-food-apartheid-america-farms-one Located in upstate New York, Soul Fire Farm is a for-profit agriculture venture and nonprofit educational space widely recognized for its “commitment to ending racism and injustice in our food system.” I scoffed a bit the first time I read the farm’s mission statement because any system without racism is almost beyond my ability to imagine. (I acknowledge I have a deep-rooted mistrust from working for too many nonprofits that let racism stand in the way of their mission.) But then I attended Penniman’s lecture at the Rhode Island School of Design last April, and I was challenged to think more deeply about the critical role of imagination in dismantling anything. To quote the cultural strategist Anasa Troutman, “If you are unable to imagine a new story . . . then how on earth are you going to have the imagination to build a whole new world?”

Speaking to a packed house, Penniman told the history of our food system through images—John Gast’s American Progress (1872), photographs of incarcerated men and migrant workers laboring in fields, portraits of Dr. Booker T. Whatley and George Washington Carver, and vintage broadsides. One of the most memorable images li/she showed was an etching depicting African women while explaining how some wove seeds into their hair before being forced to board Middle Passage slave ships. (Penniman’s pronouns are li/ya/she/he. I use li in the remainder of this piece.)3Li is the Haitian Kreyol all-gender pronoun with no possessive form. To learn more, visit the Google Doc, “Pronouns for Leah” at https://docs.google.com/document/d/13e5h2YQ98P_uStshda1xcvNNcOiNvB9jSU8g1LE7HUI/edit “Stolen land and exploited labor are the DNA strands of the food system,” li said. Penniman reminded us that American slavery wasn’t just about labor; it was about acquiring the farming knowledge of African peoples. Li touched on the different periods in centuries of white terrorism, like the rampant lynchings that prompted “the refugee crisis we romantically call The Great Migration.” Li discussed the indignities of factory farms and the invisible contributions of Spanish-language-first migrant workers who make up 85 percent of the farm labor that provides our sustenance. Penniman concluded with an invitation to the audience to reflect on our own stories and lineages in relation to the food system, encouraging us to see ourselves as more than consumers.

At the time, Penniman was on an 18-month international tour for the book Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. I spoke with li by phone a few months ago, just after the tour was cut short by the pandemic. “I wanted the book to do three things,” li explained while tending crops on the farm. “Be a practical, how-to garden guide that maybe for the first in a long time was written by not a white dude; start to rewrite the narrative of who has contributed to sustainable and regenerative agriculture in a way that uplifts the unique and precious contributions of Black, Indigenous, and people of color; and provide society as a whole, especially those with privilege, with some concrete [examples of] what you can do to create a more just food system.”

Farming While Black is an easy read yet feels biblical somehow, maybe due to the spiritual tone of the stories and lessons Penniman generously shares with the reader. It feels like a family album, too, a vibrant record of the joy and sweat that Penniman and li’s husband, Jonah, their children, Neshima and Emit, as well as staff, students, and volunteers have put into the land over the last ten years. In side columns throughout the book, Penniman situates Soul Fire Farm in a larger historical context through short backgrounders on agricultural practices and food justice influencers, including the Black Panthers, the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, and Karen Washington of Rise & Root Farm and Black Urban Growers, who wrote the book’s forward.

Highly conscious of the hero-industrial complex (the belief that a person arrives at success all alone, driven by their own genius), Penniman actively acknowledges those who came before or work alongside li, like Washington. Revered in the food world, I’ve always known Washington from afar as the woman who audaciously turned an empty lot in the Bronx into a garden long before it was the hipster-gentrifier thing to do. It was Washington who taught Penniman the concept of food apartheid. As li has said in another interview, “I would not be a farmer if it were not for [Mama Karen], because when I was a young woman—I was a teenager just getting into farming—I had a lot of doubts about whether I belonged in that movement as a Black woman.”4Karen Washington and Leah Penniman, “You Belong to the Land: A Conversation with Karen Washington and Leah Penniman,” Center for Humans and Nature. Accessed at https://www.humansandnature.org/you-belong-to-the-land-a-conversation-with-karen-washington-and-leah-penniman Washington helped li understand that Black farmers not only “have a noble legacy thousands of years old going back to the continent, but are the stewards of the future.” This resonates deeply as the COVID-19 pandemic underscores how critical farmers are to our survival and the longevity of this earth. The world as we know it is transforming and we have no idea what it will become, but the food system—how we eat, honor the land, and treat each other—is central to that transformation.

Soul Fire Farm predominantly works with African American, Indigenous, and Latinx communities. “What that means is we’re working with folks who have experienced generations of land-based trauma—slavery, sharecropping, the guest worker program, convict leasing, and more,” said Penniman. “That trauma is passed down and influences the way people relate not just to the land but to each other and to themselves, their own sense of purpose and worth and possibility. If we’re going to be in the business of calling people back to the land, part of it is paying attention to that trauma.” As much a farmer as a healer, in Farming While Black Penniman outlines the diasporic healing rituals employed at Soul Fire Farm such as dance, story circles, spiritual baths, and Haitian stone balancing. “These technologies have thrived for thousands of years because they’re very effective,” li says. “It’s important for us to make them accessible to folks who might have been disconnected previously.” Penniman’s work is art adjacent, and li’s healing practice extends to the collective Harriet’s Apothecary, founded by the artist Adaku Utah. The Apothecary members include Penniman’s sister, Naima Penniman, Soul Fire’s program director and one half of the acclaimed spoken word duo Climbing PoeTree.

Soul Fire’s work to heal historical and contemporary racialized traumas is deeper than the soil they till. In 2016, they worked with the Movement for Black Lives, contributing to the policy visions for economic justice and reparations. Then, they contributed to the Green New Deal through their work with various coalitions. More recently, they were tapped by both the Warren and Sanders campaigns to help develop their farming platforms. And Soul Fire continues to work with Heal Food Alliance, “a multi-sector, multi-racial coalition building collective power to transform our food and farm systems.” They’re also regular “rabble-rousers” around the Farm Bill. Their advocacy efforts are modeled in their own policies. For example, they’ve spent years developing relationships to establish a “cultural respect easement” that would allow Mohican citizens to use Soul Fire land, which was historically stewarded by the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of the Mohican Nation, “for ceremonies and wildcrafting in perpetuity.”

The so-called food movement promoted in mainstream media is largely driven by white folks who focus on individual choice, not systemic issues or community health. “I want us to question why we’re calling something a ‘movement’ that doesn’t center the needs of those most impacted by food injustice,” says Penniman. “We really have to be listening to the wisdom of frontline communities and making sure that they have the resources they need to thrive.” Soul Fire’s typically sold-out Farming Immersion program for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx heritage growers, and Uprooting Racism in the Food System training is where that work is most visible. The latter is not your typical diversity, equity, and inclusion training, says Penniman, because Soul Fire uses a reparations framework focused on action. As anti-racism resources are circulating online in response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others, Farming While Black is frequently cited—evidence of the book’s efficacy and definitely a sign of how much better our world would be if more people were working with the Soul Fire spirit.

Penniman cites feeding others during a summer internship at The Food Project in Boston as a turning point in li’s life as a farmer. But I wondered about li’s shift toward organizing and activism. “It’s always been,” said Penniman, from running li’s elementary school ecology club to protesting alongside li’s parents, both former members of the clergy, who were “very active” in the civil rights movement. “There are pictures of me with my crayon sign ‘No More War’ on my mom’s shoulders. I thank my parents for being that example of social justice warriors and caring deeply about community.”

Documentary film and photography—from George Stoney’s All My Babies (1953) to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s 2018 photography series for the New York Times—have played a critical role in efforts to humanize Black maternal and infant mortality statistics.

In 1951, the Georgia State Department of Public Health and the Association of American Medical Colleges commissioned filmmaker George C. Stoney to create a documentary about childbirth, specifically, the practices of Black lay midwives in the Deep South. Also known as “granny” midwives, these women were trained through apprenticeship and respected healers in their communities. With the help of community liaisons, Stoney met Mrs. Mary Francis Hill Coley (1900–1966), a midwife who is said to have delivered more than 3,000 babies in roughly 30 years. For four months, Stoney followed “Miss Mary” to her patients’ homes, observing her practice and deriving inspiration for his script. Miss Mary would become the star of his film, All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story, a bizarre period piece that merges reenactments by a mostly Black cast with midwifery instruction, a live birth, and a hymnal soundtrack.

All My Babies was intended to educate lay midwives in the Deep South, and Stoney was given a list of 118 teaching points to incorporate. But the film found a broader audience. Advertised early on as one of the “outstanding humanist works of American cinema,” All My Babies holds a place in the pantheons of film history: Stoney donated his outtakes to the Museum of Modern Art’s Film Department, which was at one time a distributor of the film. And in 2002, the Library of Congress placed All My Babies on the United States National Film Registry, calling it “a culturally, historically and artistically significant work.”

Stoney paints a familiar picture of Black subjects under the tutelage of a white “professional” or “expert.” What his film doesn’t show is how much the American medical establishment loathed—but learned—from granny midwives, drawing from their deep well of knowledge as community birth attendants before outlawing their practices. Women have always served as birth attendants, and it stands to reason that skilled birth workers in Black communities date back to ancient societies, though the literature focuses on slavery and segregation. In the antebellum years, Black midwives served their enslaved sistren and masters’ wives. Post-emancipation, they typically provided birth services to women in rural communities that lacked access to hospitals or women who feared medical establishments due to entrenched racism and, ostensibly, the decades of nonconsensual experiments on Black bodies. As Lynne Jackson writes, doctors and nurses generally looked down on lay midwives in the Deep South, recognizing them as a “temporary and unfortunate necessity.”1Lynne Jackson, The Production of George Stoney’s Film “All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story” (1952), Vol. 1, No. 4 (1987), p. 387.

Crisis Intervention

When All My Babies was released, the maternal mortality rate for Black women was 3.6 times greater than that for white women. One could speculate that Jim Crow segregation and lacking medical technologies underlie this disparity. But now, nearly 70 years later, the statistics are not much better. According to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Black women in the United States die from pregnancy-related causes at a rate 2.5 times higher than their white counterparts.2Emily E. Petersen, MD; Nicole L. Davis, Ph.D.; David Goodman, Ph.D.; Shanna Cox, MSPH; Nikki Mayes; Emily Johnston, MPH; Carla Syverson, MSN; Kristi Seed; Carrie K. Shapiro-Mendoza, Ph.D.; William M. Callaghan, MD; Wanda Barfield, MD, “Vital Signs: Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and Strategies for Prevention, 13 States, 2013–2017,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 10, 2019. (Reports in previous years showed a rate of 3.3 to 4 times higher.) Black infants face similarly horrible odds with a mortality rate more than twice that of white infants. Why does this gap exist and persist? Everyday “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” anti-Black rhetoric would have us believe that poor lifestyle choices by individual mothers is the reason for the disproportionate statistics. But multiple studies point to structural inequities, including differential access to healthcare, healthy foods, clean drinking water, reliable transportation, and safe neighborhoods. Researchers also recognize that the chronic toxic stress of racial discrimination takes a toll on the body, increasing the risk of physical health problems. And then there is the centuries-old myth that Black people are impervious to pain, a racial bias that crosses class and influences medical care—or lack thereof—in doctor’s offices and maternity wards across the country. Women’s stories of neglect include rushed cesarean sections, too little anesthesia, and failure to listen when a mother senses that she or her baby may be in danger.

Despite how much time has passed since All My Babies was created, the film continues to be germane, especially now amid a resurging demand for Black birth workers. Recent journalism has turned the spotlight on midwives and doulas of color, noting how their involvement fosters better health outcomes for Black families. (As an aside, a midwife or doula wasn’t even mentioned as an option when I was my sister’s Lamaze partner 28 years ago.) Birth workers serve as advocates for the mother but occupy different roles. Nowadays, midwives are clinically trained, licensed practitioners who deliver babies in homes and have access to hospitals if needed. Doulas are trained, unlicensed practitioners who provide emotional, physical, and educational support from pregnancy to labor to the postpartum period. In the past, a midwife might have done it all and in some countries or situations they still do.

Midwives and doulas were at the center of my recent conversation with the San Diego–based artist Andrea Chung and D’Yuanna Allen-Robb, the director of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health at the Metro Public Health Department in Nashville, for the forthcoming book Women Picturing Revolution: Representations of Black Motherhood and Photography.3Edited by Lesly Deschler Canossi and Zoraida Lopez-Diago, Women Picturing Revolution is due out in 2021. In 2018, Chung collaborated with Metro Public Health; Taneesha Reynolds, a certified nurse-midwife; and Ashley Couse, a doula and childbirth educator, to create cooking workshops for new and expectant mothers. Chung drew partial inspiration from her series, Midwives, an homage to granny midwives resulting from her research project with Dr. Alicia Bonaparte.

To understand the benefits of birth support from a public health perspective, I asked Allen-Robb, who heads a new community doula training. She named, among others, greater satisfaction in the birthing experience, lower incidences of experiencing hypertension, fewer complaints of post-surgery pain, and more reports of women returning to their healthcare provider for follow-up appointments. For Black women specifically, she spoke of the innate human need to belong and be in community. “The information shows that Black women primarily benefit from the psychosocial support and having a person or people who understand the unique experience of being Black. I know how I feel when I’m experiencing racism, and I know I’m not crazy because it’s a real thing. A mother [with a support system] might say, ‘I’m being treated differently and there is another voice or set of voices in a hospital setting who are going to advocate for me.’”

Reframing Birth Work

In this time of COVID-19, when the data tells us that the lives of the melanated and marginalized are once again overrepresented, and medical facilities are barring partners and birth workers from delivery rooms, it seems more important than ever to contemplate how the disease of racism that infects the American healthcare system has played out not only in terms of death but also in birth.

George Stoney wrote two birth scenes for All My Babies based on what he had experienced in the homes of Miss Mary’s patients. One scene was shot in a moderately well-off nuclear family home where everything was tidy and prepared. The other was shot in a shanty with the expecting couple depicted as emotionally traumatized and unprepared to welcome their child, believing it would be stillborn like their last. Swarming flies in this couple’s home suggest unsanitary conditions. “A main emphasis of the film is cleanliness and hygiene practices for the midwives,” writes Miriam Zoila Pérez. “But this emphasis foreshadows the eventual decline of the granny midwives and the messaging used to discredit them.” A combination of legislation and regulation eventually prohibited the services of granny midwives, but that was after they endured smear campaigns that portrayed them as dirty.

Stoney made efforts to exclude anything that might imply poor Black-white race relations in the American South or that might be seen as a northerner’s attempt to “exploit Southern poverty.” Despite—or maybe because of—what Stoney left out, All My Babies was lauded for its uniqueness, particularly for the way Stoney positioned granny midwives as respectable members of society. In later interviews, Stoney recalled comments that he had “heightened these people.” His editor said to him, “You have shown them so that I don’t think of them as Negroes, but just people.”4Lynne Jackson, The Production of George Stoney’s Film “All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story” (1952), Vol. 1, No. 4 (1987), p. 386.

Documentary film and photography have played a critical role in recent efforts to humanize Black maternal and infant mortality statistics. Take, for example, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photography for Linda Villarosa’s 2018 New York Times article, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” Frazier chronicled the pregnancy of Villarosa’s main subject, Simone Landrum, a New Orleans–based mother preparing to welcome her third child after the loss of her previous child. Two photographs spotlight the relationship between Landrum and her doula, Latona Giwa (co-founder of Birthmark Doula Collective). Working in the lineage of granny midwives, Giwa represents a life-affirming bridge in the mother-child-doctor relationship.

Frazier’s images echo something that Stoney wanted to portray: a celebration of childbirth and family as opposed to a depiction of trauma. “There are ways to say through photographs, ‘We are strong. We are supporting one another. We raise healthy children. We have this expectation for our families, and not only for our families, we have this expectation of the system around us,’” says Allen-Robb. “When we expect more, we demand more, and we hold people accountable for delivering on the more that we expect and demand. Photography, and images of Black women specifically, can be extremely powerful in not only systems shift, but also in helping us as a collective of individuals shift our own internalized thinking.” I would argue that the best art goes a step further and motivates people to action—which we need more of from all sectors of health and humanities because mothers and babies are dying unnecessarily.